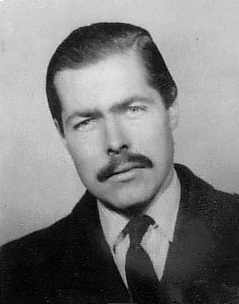

The disappearance of Lord Lucan is one of the most intriguing mysteries in modern British history.

Richard John Bingham, 7th Earl of Lucan, was 40 when he fled justice after the murder of his children’s nanny Sandra Rivett on November 8 1974.

He has never been seen since, although countless theories have sprung up as to what actually happened to him.

Some believe he killed himself in the sea off the coast of Newhaven. Others claim he started a new life abroad, either in South Africa, Goa or New Zealand. Officially, he was declared dead in October 1999.

Known as ‘Lucky’ Lucan because of his fondness for gambling, he was educated at Eton College and served in the Coldstream Guards before taking up the earldom on the death of his father, a hereditary peer in the House of Lords.

By 1974 he had separated from his wife, Countess Veronica Lucan, who was living with their three children at 46 Lower Belgrave Street.

At 9.45pm on Thursday, November 7, the countess burst into a nearby pub, the Plumber’s Arms, and shouted: ‘Murder, murder! He’s tried to kill me!’

She was bleeding from wounds to her head and was taken to hospital after collapsing unconscious.

Police broke into the house and found the children unharmed – two were asleep and a third was watching TV in her bedroom.

But when officers went down to the basement they found blood splashed on the wall, bloody footprints and a canvas bag containing the body of Sandra Rivett.

She had severe injuries to the back of her head, most probably caused by a piece of lead piping wrapped with tape found nearby.

Lucan’s wife was later to tell police that she had been watching Mastermind on TV when the nanny asked her if she wanted a cup of tea.

When 29 year-old Miss Rivett did not return with the drink she went into the hallway to investigate.

At the top of the stairs leading down the basement she noticed the light switch did not work and called Sandra’s name. Suddenly she was beaten over the head with a heavy object.

The countess explained that she recognised her attacker as her husband and managed to fight him off by grabbing his testicles. According to her statement to police he then calmed down and admitted the nanny was dead.

She has later admitted that she offered to help him conceal the body but then seized her chance to escape when he went to the bathroom to fetch a cloth to tend to her wounds.

Many, including the countess himself, believe that Lucan mistook the nanny for his wife in the darkness, having taken out the lightbulb in preparation for his attack.

Lucan certainly had a motive – his wife had won custody of the children a year earlier and he had been left heavily in debt. He is said to have expressed a desire to kill her in conversations with two friends.

When police went to Lucan’s apartment in Elizabeth Street he was already gone, although his car keys, passport and driving licence were still in the flat.

He is known to have turned up at a friend’s home and made several phone calls, including one to his mother. He also wrote two letters to his sister-in-law’s husband, in which he claimed to have interrupted a fight between his wife and an intruder.

Lucan suggested his wife was paranoid and added: ‘The circumstantial evidence against me is strong in that V. will say it was all my doing and I will lie doggo for a while, but I am only concerned about the children.’

He was last seen at 1.15am driving away in a Ford Corsair, which was found three days later abandoned on the coast near Newhaven. One of his last acts was to write another letter to his friend Michael Stoop, who had lent him the car, which began: ‘I have had a traumatic night of unbelievable coincidences.’

His version of events were rejected in June 1975 by the inquest jury, who publicly named Lucan as the murderer. A month later a bill was passed banning coroner’s courts from identifying the killer, making it the last such verdict in the UK.

While there have since been thousands of sightings of him all over the world, none have been confirmed and police have not uncovered any proof he is still alive.

Lucan’s wife makes her position clear on her website: ‘I have publicly stated since 1987 that my late husband is not alive and I sometimes use the prefix ‘dowager’ to make my position clear which is that of a widow.’

Then in 2012 a witness came forward to say she arranged for Lucan’s children to fly to Africa between 1979 and 1981 so that he could see them from a distance.

Whatever the truth, the name of Lord Lucan, like that of the missing racehorse Shergar, has passed into folklore.

_______

There are many books which tell the story of Lord Lucan in detail, including Dead Lucky – Lord Lucan: The Final Truth by Duncan MacLaughlin.

Further detail on the case can be found online at the Crime Library website and Wikipedia.

The Countess of Lucan has also set up a website in an attempt to counter conspiracy theories, called Setting the Record Straight. The passport photo of Lord Lucan used to illustrate this article can be found there among other family photographs.