Detectives described it as “a very brutal murder… in an average residential street in suburbia”. Yet just three months later they closed their active investigation, unable to establish a motive or identify a suspect. The case remains unsolved more than 30 years later.

The victim was James Durrant, a relatively wealthy 74-year-old retired solicitor who lived with his wife Margaret, 77, in Surbiton, southwest London, and had recently celebrated his 50th wedding anniversary. He was within a month of seeing his 75th birthday and was not known for his risk-taking, possibly having seen enough action as a squadron leader with the RAF during the Second World War. His son Christopher, then aged 42, described him as “a quiet elderly man who was beginning to suffer in health a little… life did not expose him to situations where he would be pushed around – for example at football matches.”

On the evening of 26 October 1988 Durrant attended a Masonic function at the Connaught Rooms in Covent Garden in his role as treasurer of the Anglo-Dutch lodge (established 1942, erased 2014 due to lack of members). He then had dinner with friends at the Sugar Loaf pub at 40 Great Queen Street (now Philomena’s Irish Bar and Kitchen) before heading home at around 8.30pm.

The first puzzle is how he got to Surbiton. Did he get a train from Waterloo? It appears there were no definite witnesses to his journey apart from a possible sighting at Surbiton station.

That evening his wife Margaret was visiting their son Christopher for dinner. Later that night, concerned that he had not made contact, she and Christopher decided to head back to the couple’s home at 12 Cranes Park Avenue. After entering the three-bedroom house shortly before midnight, they discovered James Durrant lying dead on the floor.

He had been killed with a single blow to the front of the head with a heavy, blunt but smooth edged weapon similar to a baseball bat. He had also suffered a knife wound to the upper half of his body, according to newspaper reports. There may also have been other, undisclosed injuries.

Detectives found no sign of forced entry, suggesting he was either surprised when he entered the house or was accompanied by the killer as he made his way inside. Nothing was missing from the scene other than his dark leather wallet containing cash and miscellaneous correspondence, which suggested that the motive was unlikely to be robbery. The killer had not bothered to take other cash found on the body. The porch door had been closed but left unlocked after the murder. Neither of the murder weapons had been left at the scene.

At a press conference a few days later, Margaret Durrant described the killing as “very puzzling”. She was not aware of anything that might suggest he was in danger and rejected any suggesting that there was a link to his membership of the Masons. Instead she and Christopher claimed that the killer could have been a drug addict or someone in need of money who followed the victim home from the railway station.

“Somebody out there must know something,” Christopher told reporters. “Someone must be sheltering someone. Someone must know of a connection who can help us.”

The police officer leading the investigation, Detective Superintendent Malcolm Butcher, gave the local newspaper the impression he was working on the theory that James Durrant may have known his killer. “This was a very brutal murder,” he told the Kingston Informer. “The motive may not have been robbery. It could have been motiveless. It occurred in an average residential street in suburbia inside the security of someone’s home. The killer went over the top, even after death, and may suggest the type of person involved.” He added: “Someone left the hosue with blood on them carrying both weapons, and we are anxious to hear from anyone who can help”.

Police questioned commuters at both Waterloo and Surbiton stations in the week after the murder but were apparently unable to establish the victim’s route home.

A reconstruction of the case was also featured on BBC’s Crimewatch TV programme in the hope of finding crucial witnesses, apparently without success. According to the Kingston Informer of 2 December 1988 police were “no nearer knowing the last movements” of the victim and had been unable to unearth any leads on the Isle of Man, where James Durrant owned property.

After exhausting all their leads, police “terminated” the active inquiry in January 1989, the newspaper reported.

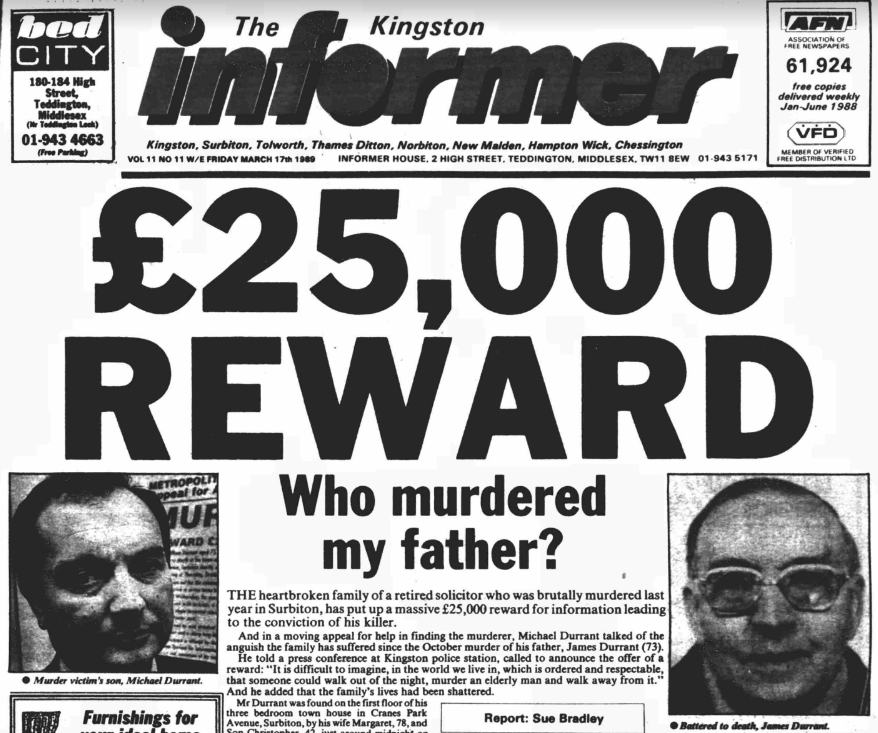

The family, concerned at the lack of progress, issued their own appeal on the first anniversay of the case and offered a £25,000 reward for information.

Son Michael Durrant, then a 47-year-old chartered surveyor, spoke to reporters at Kingston Police station. “It is difficult to imagine in the world we live in, which is ordered and respectable, that someone could walk out of the night, murder and elderly man and walk away from it,” he said.

“It is difficult to believe that it happened. And it is difficult to believe that despite enquiries there is no identity of the cultprit. It is a very unsatisfactory state of affairs. It is difficult to cope with living and not knowing the culprit’s identity. Someone must have seen him. If this can happen and they get away with it, how do you know it is not going to happen again? It must not be allowed to. We are sincerely hoping the reward will bring some information.”

Christopher revealed his mother was still deeply affected by the crime and was not sleeping properly. “She cannot look at pictures of him,” he said. “She kept thinking he would walk back through the door.”

The murder remains unsolved and has received little attention since, other than a short article in the Daily Mail which suggested police were examining possible links to the cases of Deborah Linsley, who was stabbed to death on a train in March 1988, and Alison Shaughnessy, who was stabbed to death at her home in Battersea in 1991. However there seems to be no evidence of any connection apart from the fact they all made train journeys on the days they died.